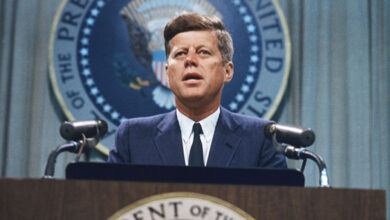

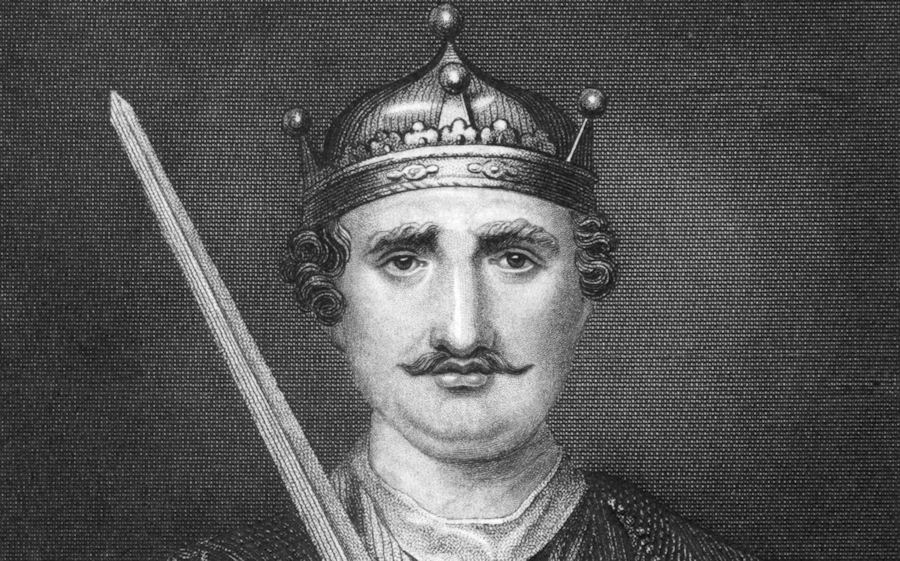

“Life yields only to be conqueror. Never accept what can be gained by giving in.” – William the Conqueror

England’s first King William became known as The Conqueror and has achieved legendary status in terms of the history of England. Although he lived a thousand years ago we know a surprising amount about his life. In the ten centuries since his reign, many monarchs have come and gone and a few of them can legitimately claim to have changed history. King William I is one of those, and what changes he made. Following his successful invasion of England, he arguably created the English nobility and a society that we are still familiar with today.

The man who would become King William I of England was born in 1028 (or maybe 1027 depending upon the sources you read), in Falaise, in the Duchy of Normandy, in the northwest of France. His father was Duke Robert I of Normandy. Although the Duke was not married to William’s mother, Herleva, William was the Duke’s only son and thus would inherit his father’s title, even though there were a few who tried to fight his claim due to the fact that his father had himself inherited the title under somewhat dubious circumstances. He was accused at the time of killing his elder brother Richard III Duke of Normandy, who had himself only inherited the title the previous year, as he and Robert had been at each other’s throats for years. The suspicious timing of Richard’s death made Robert’s position somewhat precarious as he was seen by some to not be the rightful Duke. The other problem that could jeopardise the young William’s succession was that if his father Robert decided to marry, any offspring would have a more legitimate claim than he. But this never happened. So, even though he was illegitimate, with no serious rivals, William inherited the Dukedom in 1035 when his father Robert died in Nicaea, a town which is now called İznik, whilst on his way back to Normandy from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

Remembering that he was only seven or eight years old when he inherited the Dukedom, William became a pawn during his early years as different nobles used their custody of the young boy to jostle for positions of power in the duchy. Fortunately, William had some powerful friends and protectors including his great uncle, Archbishop Robert, and just as importantly his claim also had the support of the French King, Henry I. However, when his great uncle died in 1037, one of William’s strongest allies and protectors was lost to him and his position once again was under threat.

The uncertainty around the legitimacy of William’s claim and the fact that he had lost one of his most important supporters led to a certain amount of anarchy, and for quite a while lawlessness reigned in Normandy. A succession of nobles continued to take custody of young William and as each one either died or was killed, sometimes within months of the previous custodian, power continued to shift. Although proxy wars were fought, and lands changed hands, all who came acknowledged William’s right to rule and his title, at least in theory. However, the battles fought on his behalf had bred true resentment and there were some who sought to overthrow William from his tenuous ducal government.

The biggest threat of all came with the rebellion of Guy of Burgundy and various other noblemen who supported him and sought to depose the young William. Although many of the accounts appear to have been embellished with time, one thing seems fairly certain and that was that William, with the support of King Henry I, fought the decisive Battle of Val-ès-Dunes near Caen and with this victory, the rebellion was put down and William took control of Normandy. It wasn’t the end of the fighting though and William found himself almost constantly fighting with the nobility.

William, though, was not content to be a mere pawn in early medieval France and had aspirations of his own. By the 1050s he was gaining serious support, partly by his marriage to Matilda of Flanders who was the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders. Although it is possible the marriage was wholly un-sanctioned by the Pope, the union did not seem to have particularly damaged the relationship between Normandy and the church in Rome. More importantly, his marriage gave William a powerful ally in the Count and by the end of 1060, William was able to appoint many supporters in strategic positions of power who would support him in exerting his claims and rights and the infighting would finally come to an end in Normandy, allowing William to concentrate on other ambitions.

The first of these came in the year 1062 when the count of Maine died. Maine was a county (now a French province), on William’s Western border. In order to gain support in this region and thus protect his border, William had earlier betrothed his eldest son to the Count’s sister, Margaret, but when the Count, Herbert II died, an unsuccessful claim on the county by William, through his son, led to him invading. He took total control of the area by 1064. Successfully seizing control of Maine made his own position in Normandy more secure but gave William a far more important resource for his future conquests and that was manpower. As the unquestioned Duke of Normandy, William exerted huge power and influence. Both a clever tactician as well as fearlessly brave, William regularly led his own men into battle and did so for nearly his entire life. His days were now fairly content following the squabble and strife of the near continent over the previous decade and a half. He even managed to enjoy time in the loving companionship of his wife Matilda.

Unusual for medieval monarchs, William appears to have been completely infatuated with his wife and there is no known record of his ever being unfaithful to her. King William’s personal life has always been considered to be practically beyond reproach. Honourable, selfless, and a dedicated moralist, William constantly strove to maintain his moral code. However, to the degree that he sought to better his inner self and elevate his own personal morality, the morality that he showed to his enemies was of quite a different flavour. Many medieval historians contemporary and afterward have reported that William was decisively vicious when it came to putting down rebellions and all who opposed him. Many individuals could attest to the cruelty that William would show to those, who were not in his favour.

The real challenge for William came in the year 1066 when the King of England, Edward the Confessor died without having produced a natural heir to the English throne. William, the Duke of Normandy, was a viable potential successor as he was the grandson of Edward’s maternal uncle, Richard II, Duke of Normandy. William believed that this gave him a strong claim to the English throne and one made stronger still by the apparent choice by King Edward to name William as his successor. Records of this decision actually being made are sketchy at best, but it was a decision which was apparently made by the King in the year 1051. Obviously, William was not the only claimant. There were others, specifically Godwin the Earl of Wessex and his son Harold.

Godwin was a member of one of the powerful ruling families of England and King Edward had actually married Godwin’s daughter in the year 1043. Godwin was a huge supporter of Edward’s ascension to the throne. However, a spoiling of the relationship between them saw Godwin sent into exile, but he was able to force his way back with the support of a small army and make peace with King Edward. However, it was not Godwin who would strife with William for the future throne and crown of England but his son Harold. Upon the death of Godwin in 1053, his son Harold succeeded to his father’s estate and title. According to some sources, right before his death, King Edward supposedly made Harold the future king. This story was not contested by the Normans but what was contested was that a later decision made by the King could not nullify one that was made earlier, especially as that earlier decision was made when the King was of sounder mind and body.

The idea of a French nobleman ruling as the King of England did not sit well with the local barons who sought to preserve their own familial power and traditional rights and so it was decided that Edward’s later decision would stand, and so Harold was crowned on 6 January 1066 in the then new Westminster Abbey. William believed he had the more credible claim to the throne and so he decided to embark on a mission to make the throne his, which if it could not be gained through politics, would be gained through military might. A king was only a king if he could defend his kingdom, and William set about building a naval flotilla capable of moving himself and his army across the channel to England. William was in an exceptional location for this endeavour. Had he been a duke in another area of France, such an operation would have been far more difficult, if not impossible. However, being the Duke of Normandy, he was perfectly positioned to have his armies and fleets conveniently consolidated for an attack on England.

Early in the year 1066 after the ascension of Harold to the English throne, William met with his barons to discuss the invasion of England. Some sources make the claim that this was a debate, but this is almost certainly fictitious as not only did William have full control over his nobles and supporters at this point, but also the nobility would likely have been enthralled about the possibility of the riches to be gained by a conquest of England. William spent the better part of the summer of 1066 assembling a huge army and fleet. Some claim that the fleet may have numbered as many as three thousand ships although this is almost certainly an exaggeration. Modern historians are unsure exactly where William the Conqueror built his fleet, but one thing is for certain, and that is that it was built and did successfully bring troops over to England to fight the English army, already weakened from having fought back multiple Danish incursions.

King Harold, the then ruling king of England, was in a weakened state. He was already in the process of fighting off a Danish invasion in the summer and autumn of 1066 from the north when William took the opportunity to launch a southern invasion at the same time. King Harold managed to defeat the northern army but was unable to race down the country in time or with sufficient strength in his men to put up a solid defence against William. William, on the other hand, had taken the opportunity afforded by Harold’s tardiness to build fortifications at Hastings as well as maraud across some of the interior of England. William didn’t venture too far though as he didn’t want to travel far from the sea as his lines of communication would be strained if he did so. William’s support at this time came exclusively from the continent and so ensuring that his army could be supplied by sea was essential to ensuring his success in the campaign.

On the morning of 14 October 1066, the battle which would become known as The Battle of Hastings commenced although the exact detail of how the battle evolved are blurred due to contradicting sources. It appears that the two armies, which were of approximately equal size at various times each gained advantages. Details are even muddier regarding what happened in the afternoon, but it seems clear that the decisive event was the death of Harold. Accounts differ regarding how Harold met his end, with one story being that he was killed at the hands of William and if the Bayeux Tapestry is to be believed he may have died as the result of an arrow through his eye. His body was identified the following day.

Having invaded in September and with the Battle of Hastings fought in October, William proceeded to consolidate his position. He took Dover and Canterbury and secure the royal treasury at Winchester. He then marched on London and arrived in Southwark by November. Any other resistance steadily fell and William had crossed the River Thames by early December. He was crowned in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. His swift suppression of the English army and feudal lords was a tribute to his leadership and cunning. After having put down a few more minor rebellions and insurrections, King William retired to the continent and would rarely visit England. The rest of his life would be spent protecting and defending his positions but primarily on the continent where various rebellions and power plays would continue throughout the rest of his life.

King William gained the moniker the Conqueror for his conquest of England and he enjoyed strength and good health for the next twenty years but whilst on a campaign in France to seize Mantes he either injured himself on the pommel of his saddle or inexplicably fell ill. He was taken to the priory of Saint Gervase in Rouen. He died on 9 September 1087.

England had become thoroughly Norman by his conquest and the placing of Norman nobility into places of power. England would remain Norman following William’s death as he left the care of the kingdom to his second son, who would become William II.

William I’s speed and ferocity, as well as the long-term historical changes he made, puts him in a special place among the monarchy of a new English dynasty, one that has shaped and changed the nature, character, and culture of England for the last thousand years.